A step forward.

In 2008 and 2010, California voters went to the ballot box and voted on three electoral reform measures. The reformers won all three ballots.

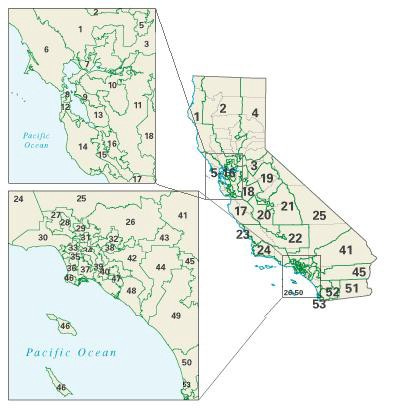

Proposition 11 established the California Citizens Redistricting Commission (CCRC) and gave it the power to draw legislative districts.

Proposition 14 established the top-two primary system.

Proposition 20 expanded the CCRC’s mandate to include Congressional maps.

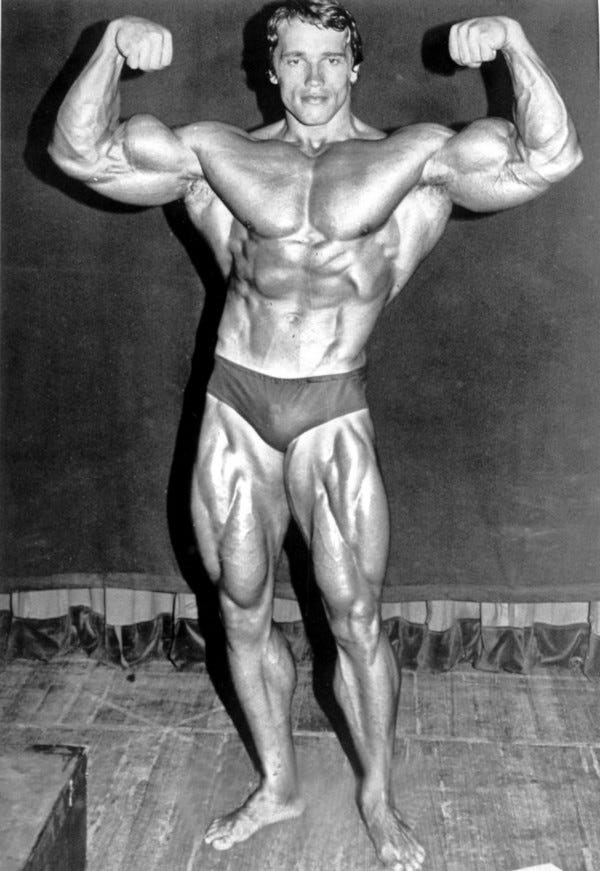

The most prominent supporter of all elements of this reform package was Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger, a non-traditional Republican who had been initially elected in a way that bypassed the normal primary process. As noted above, these reforms were passed into law by the voters of California directly. They did not go through the normal legislative process.

It has recently become fashionable in certain circles to claim that this reform package was an attempt by the Democratic Party to consolidate power unfairly in California. This is materially, factually, and historically false.

Proposition 11 was opposed by the California Democratic Party. Proposition 14 was opposed by basically every Californian political party. A large number of Congressional Democrats and donors lined up to support a referendum getting rid of the CCRC (Proposition 27) as an opposing measure to Proposition 20.

Voters hoped that both the CCRC and the top-two system would lead to more competitive elections and better representation of the shifting views of Californians. These hopes have been proven correct.

The success of the CCRC

Before the CCRC, California’s districts had noteworthy characteristics. They were very insensitive to changes in vote total, with very few competitive seats — it was a massive bipartisan pro-incumbent gerrymander designed to maintain the status quo.

It’s worth noting that even single-party gerrymanders are designed to create very static maps, with safe districts for both parties.

For example, in the 2008 elections, the popular margin in Congressional races in California was 23%. In the 2010 elections, the margin was 10%. Both elections sent a 34D-19R delegation to Congress in spite of the huge shift in voting patterns. With fair maps and ordinary distortions due to single-member districts, 23% and 10% margins would most likely correspond to 39D-14R and 32D-21R delegations. Out of 265 elections carried out in the 2002–2010 cycle, only two Congressional districts changed hands.

The CCRC drew districts that were more compact and more competitive. As a result of greater competitiveness, they were also more responsive to shifts in California’s voting patterns.

California’s Congressional delegation became more Democratic and less Republican over the course of the 2012–2020 cycle simply because Democrats won more votes in California over time.

This responsiveness can be seen in both directions. Republicans gain three seats in 2020 — more than changed hands from 2002 to 2010 in total. On the level of the state legislature, the success story is the same: Districts were more compact and more competitive.

Top-two elections

As noted above, top-two elections were vigorously opposed by California’s major and minor political parties. Both Democratic and Republican critics of the system focus on cases where the final round features two candidates of the same party. There is evidence that some voters sit out the second round in this case, although they still show up to the polls. Selectively not voting in a race is known as roll-off.

These same party runoffs are relatively rare (they’re not expected to be common until the minority party earns less than half the vote of the majority party), and mostly occur in contests where a two-party race between a Democrat and a Republican would not be competitive.

If we look at the bigger picture, voter roll-off has not gotten worse since the implementation of California’s 2010 round of electoral reform. Contrariwise, it has trended downwards for both State Assembly and House of Representatives races. Even if some voters don’t care who wins an intraparty contest, most voters find they have fewer reasons to ignore downballot races.

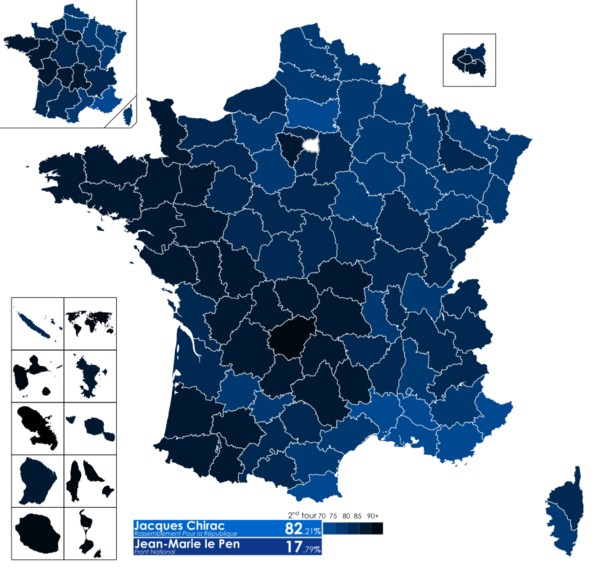

It’s worth noting that the top two primary system is not an experimental and untested system. It is, in fact, very similar to the majority runoff systems used widely in many other places — for example, Louisiana and France.

The largest difference between California’s current election system and the French presidential election system is that the second round runoff between the top two candidates is not optional in California, even if a candidate wins an outright majority of the vote during the first round.

The way forward

The reforms adopted by California have led to significant improvements in how well California chooses politicians to represent the views of its voters. These reforms were actively opposed by California’s political establishment and continue to draw fire from partisan loyalists from both parties, in spite of the fact that they have been successful at achieving their goals. Elections are now more competitive and elect more moderate politicians who are closer to the median voter they represent.

It’s possible the CCRC could be improved. One of the major potential issues is the set of criteria used for drawing district lines — most controversially, the use and possible abuse of loosely-defined “communities of interest.” However, the main sources of disproportionality in Californian elections are the distortions caused by the use of single member districts instead of a proportional representation system. Finally, abolishing the CCRC would mean overt gerrymandering by the Democratic majority in the state legislature.

The top two system has a clearer and more pronounced flaw. While the second round (majority runoff) between two candidates is straightforward and a strong safeguard against the election of very unpopular candidates, the first round plurality vote is flawed. The study of voting systems shows us that there are many better alternatives to a plurality vote when you have more than two candidates. This is also a flaw of the partisan primary system: Extremists can win partisan primaries with the support of a minority of their own party.

In other words, the flaws in California’s electoral reforms (including both the districting system and the top two election system) are flaws that were already present in the existing system.