Electability & the blue bubble

I’ve been following the pre-primary process closely as Democratic candidates work the ground in Iowa & other states in preparation for the…

This article was initially written early in October 2019. Notably, Beto O’Rourke dropped out shortly afterwards.

I’ve been following the pre-primary process closely as Democratic candidates work the ground in Iowa & other states in preparation for the primary elections. I’ve also been thinking a lot about the issue of electability, and potential mistakes being made by Democrat-friendly media outlets.

So. First, I’m going to talk a little bit about how I’m seeing the primary talked about in blue media, ranging from wonkish (e.g., FiveThirtyEight) to mainstream (e.g., MSNBC, Washington Post, NPR). Second, I’m going to talk about electability and what evidence we have available. Third, I’m going to tie together the separate pieces of evidence and say what it means about candidates’ electability.

Right now, with impeachment hearings underway, the election environment is very difficult to predict in advance. The 1976 and 2000 elections were both quite close. Impeachment could backfire on Democrats; it could sink the Republicans; it could also trigger one of the periodic breakdowns of the two-party system and lead to a highly unpredictable three or four candidate race. Any of the candidates might win or lose if nominated. In a certain sense, every candidate is electable.

It’s also worth keeping in mind that the popularity of a presidential candidate can also have effects downballot. 11 governors, 35 senators, 435 representatives, and 89 state legislative chambers in 46 different states will be elected in 2020. The stakes are even higher because 2020 is a census year; the state governments in place after the 2020 election will determine how districts are drawn in the wake of the decennial census. Winning the presidency isn’t the only thing that matters in choosing a presidential candidate.

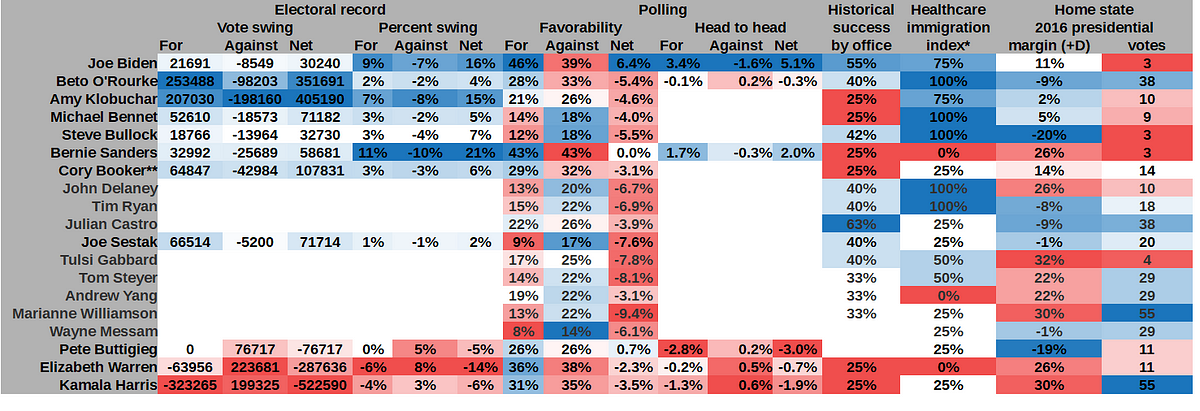

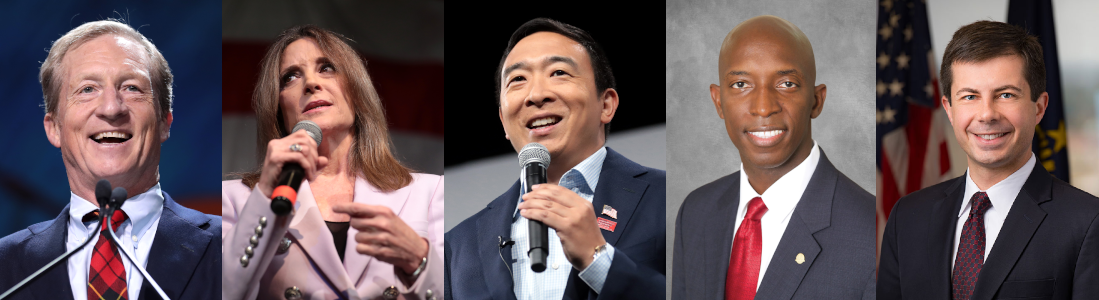

There are nineteen major candidates in the race, by some accountings; this is a big field. One candidate is a governor, two served in the Obama administration, six are sitting senators, five others have had experience in Congress, and five are wild card candidates with a thin political resume.

Joe Biden is the most obviously and clearly electable candidate. If Biden leaves the field due to scandal, health problems, or impending loss, it’s not clear who else in the field might be as electable as Biden appears to be right now. Similarly, for voters who dislike Biden but think that winning is the highest priority, it’s not clear who is a good alternative. The indicators are not bad but not quite as strong for Bernie Sanders, though given his recent heart attack, any voters concerned about Biden’s age have even more reason to be leery of Sanders’s age.

If you’re looking for a candidate who might be electable than Biden or Sanders, then there are four clear alternatives to consider: Amy Klobuchar, Beto O’Rourke, Michael Bennet, and Steve Bullock. In each case, there are several good reasons to consider the candidate to be likely electable, even if they are still mostly unknown by the national electorate.

The candidates that have more favorable media coverage within the blue bubble seem less electable outside of it. Senators Elizabeth Warren and Kamala Harris decisively do not appear to be electable candidates, and the indicators are at best mixed for Pete Buttigieg. The historical record provides strong reasons for pessimism about the prospects of sitting senators or the unprecedented case of a mayor running for president. That’s not to say that they can’t win — or that they might have better than even odds against Trump — but their odds look worse than those of other candidates.

Horse race coverage & the blue bubble.

Most of the coverage of the Democratic primaries has revolved around talking about the primary as a race: Who seems most likely to win? Who has an advantage in key early states? Who is raising money and gaining endorsements? What do Democratic voters think about the candidates?

A much more important question, both for Democrats and for others, is this: How well are the Democratic candidates doing at gaining support among the population as a whole? In other words, how electable are they?

While there are some swing voters and sporadic voters inside of the Democratic primary electorate (e.g., see page 9 of this paper; in the general election in 2008, 19% Democratic primary supporters voted for McCain and 5% stayed home), the Democratic primary electorate simply is not representative of the electorate as a whole. A strong candidate, like Barack Obama, will win votes from many voters willing to vote for Republican candidates.

For Democrats and for blue media, horse race coverage stays naturally within bubbles where almost everyone is a Democrat. It’s dangerously easy for partisans to believe that voters unlike them don’t matter, or that their opponents are fated to lose in the presidential election. If everybody you talk to thinks the same way as you do, it’s easy to ignore those who don’t.

Blue bubbles are partly geographic and partly communicative; there’s been a significant rise in political segregation into “blue” and “red” areas. Many blue media outlets are either on the Pacific coast or the Acela Corridor from D.C. to Boston; successful candidates usually come from large states, and a home state edge in a battleground state or region may come with an Electoral College advantage.

How to think about electability

The easy votes for a Democratic candidate to win are usually the Democratic ones. The harder votes to get to tend to come from independent voters and Republicans. This is the difference between stronger candidates like Barack Obama (who won 53% of the vote in 2008) and weaker candidates like Hillary Clinton (who won 48% of the vote in 2016).

There are three ways to think about electability. First, we can look at history to provide examples. Second, we can look at the fundamental basics that influence popularity. Third, we can look at polling of the general population, covering issues and candidates.

Blue media has been concentrating more on polls of Democrats than polls of the general population. FiveThirtyEight has published two articles telling people not to pay attention to head-to-head polls, and they don’t even cover favorability polling of Democratic candidates in their poll tracking.

While the shifts in public opinion towards Democrats and Republicans over the next year are difficult to predict ahead of time, current opinions are the major source of available information, and they’re at least no worse than relying on subjective hunches based on personal biases.

Favorability polling

The simplest question you can ask in a poll is this: Do you like X or not?

Candidates’ favorability ratings among the general population should track with how electable they were. The problem is that if the share of the population that knows anything about a candidate is small, the responses you get are less meaningful — either “I don’t know” or a freshly fabricated opinion courtesy of the demand effect — and may be disproportionately tilted one way or another.

Complicating matters further, these polls don’t seem to be the most fashionable sort of poll right now. We have more limited data, in other words.

Most contenders have averaged net negative favorability in the polls I’ve looked at. The exceptions are Joe Biden, with significantly net positive favorability; Pete Buttigieg, with narrowly positive numbers; and Bernie Sanders, who has averaged very close to equal favorable and unfavorable ratings. Overall, this is not good news for Democratic candidates, except for Joe Biden, who stands out.

Head to head polling

Variation in samples and techniques sampled population lead to fairly significant variations in polling. If we concentrate on polls that compare multiple Democratic candidates to Trump, however, we can tease out any general partisan lean to the poll’s outcome and focus on the respondents who care about the differences between the Democratic candidates.

By subtracting the median vote for Trump and the median vote for any Democratic candidate out of a set of polls, we get a much sharper picture of the differences among Democratic candidates, with few visible outliers. Out of the six most commonly-polled candidates, there’s a consistent pattern that Joe Biden usually does best, followed by Bernie Sanders. The fact that this pattern is more consistent than the raw head to head polling suggests that the differences are indeed meaningful.

Third place in terms of keeping his own support high and Trump support low is Beto O’Rourke. Head to head polling in Texas sometimes has even suggested he would do better than Biden in Texas.

Down in the negative end of the range, Elizabeth Warren tends to do better than Kamala Harris, and Pete Buttigieg seems to do the worst in head to head polls. Interestingly, out of the six frequently-polled candidates, the three candidates who do the worst in head to head polls are the ones who have had the most disproportionately glowing coverage in blue media outlets.

Past election performance

A candidate who has done well in the past is likely to do well again. The main complication in trying to predict a presidential election from past electoral history of the candidate is that national, state, and local electorates differ.

It’s possible to control for the difference in partisanship, though. I have compared candidates’ electoral performance against Republicans in statewide races to the performance of other politicians running against Republicans in the same states in the same year.

Amy Klobuchar stands out more than any other candidate by this metric. Beto O’Rourke also quite clearly outperformed every single other Democratic candidates in Texas in 2018, and arguably every Democratic candidate in Texas for the last twenty years. Michael Bennet has also done consistently well.

Joe Biden, Bernie Sanders, and Steve Bullock have all had a pattern of consistent but not unprecedented performance in small states where Democrats did not perform consistently. It’s not unusual to see large amounts of ticket-splitting in Delaware, Vermont, and Montana.

In other words, most of the experienced politicians running for president have a strong record of electoral performance. There are two major exceptions, however — exactly the same two candidates who have been doing badly in head-to-head polling.

Elizabeth Warren did badly in both of her races compared to most other Democrats running in her state at the same time. Kamala Harris has had a mixed electoral record against Republicans: In her initial bid for the office of Attorney General in 2010, she did very badly, almost losing in a state where Democrats easily swept all other statewide contests. In 2014, as an incumbent in a lower-turnout election, her performance was close to the middle of the Democratic pack.

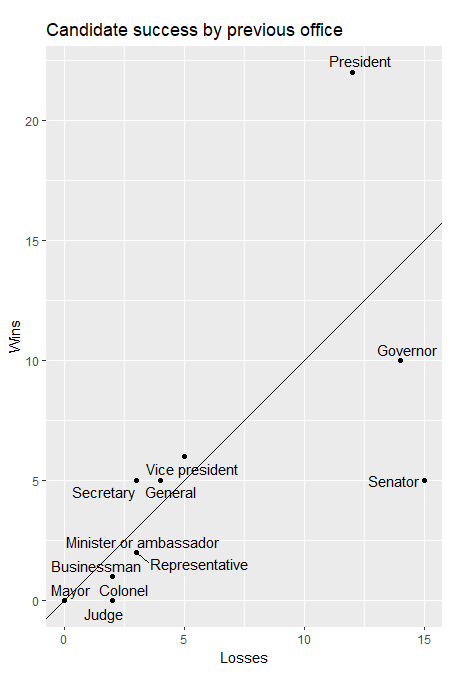

Previous office held

Vice presidents and other members of a previous administration (secretaries, ministers, and ambassadors) account for twenty-four major presidential candidates, including thirteen winners (a 54% win rate).

For the sitting senators running for the nomination, the pessimistic reality is that current and recent senators have only won five presidential races out of twenty attempts. This is one of the most statistically striking patterns in American presidential elections.

Governors and representatives are the only other type of candidate in our current pool of options to have won more than once. Representatives running for office usually either narrowly lost a nationally prominent Senate race or held prominent leadership positions in the House (e.g., speaker, minority leader).

No mayor has ever qualified as a major presidential candidate, and only three major candidates have ever lacked the usual political or military backgrounds — Donald Trump in 2016 being the only one of those three candidates to win.

From a historical perspective, this information is generally favorable for Joe Biden, Julian Castro, Steve Bullock, Beto O’Rourke, and other current and former representatives over the senators and wild card candidates.

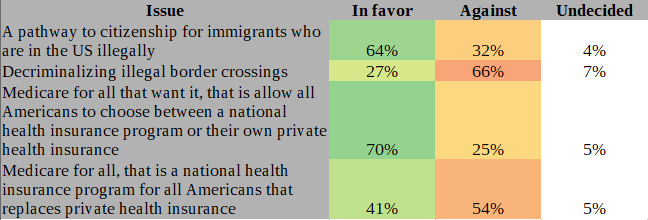

The issues

Basic game theoretic analysis shows that when it comes to the issues, it is generally beneficial to choose positions that are closer to the median of the population. In dealing with homo sapiens rather than homo economicus, it’s worth noting that many voters don’t vote based on the issues. However, some voters do, and there are a few key issues that are very important on which the Democratic candidates differ from one another.

Two that are in particularly bright focus are health care and immigration. A majority of the population supports a public option for health care; a majority opposes banning private insurance. A majority of the population supports a pathway to citizenship for existing immigrants; a majority does not support decriminalizing border crossings.

On these two issues, there are three problems with the more radical position. First, some voters do vote based on these issues, so you will likely lose some voters by taking a very unpopular position.

Second, in all of these cases, almost all Democratic candidates back related positions that are broadly acceptable to both Democratic voters and the general public, and represent sweeping progressive reforms of the status quo.

Third, sweeping reforms are difficult, even if Democrats hold the White House and majorities in both houses of Congress. See 2009–2010, 1993–1994, and 1977–1980 for historical examples.

The candidates who have stayed away from embracing either of the two major losing positions are in a stronger position here. This is not the full picture of issue strength, but it’s a simple snapshot.

The big picture

We have a lot of information that points towards Joe Biden being more electable than Bernie Sanders, and towards Bernie Sanders being more electable than Elizabeth Warren or Kamala Harris. Our information on the other fifteen major candidates is less clear.

That’s not to say that Joe Biden is necessarily the most electable candidate: He’s just the one with the strongest indicators. Who might be more electable? Let’s go down the list.

The senator candidates

Historically, senators are often bad candidates, but there are exceptions. As I mentioned above, Elizabeth Warren and Kamala Harris stand out in a bad way on the chart. Cory Booker is also a senator from a safely Democratic state; however, he’s tried harder to reach out to the middle. It’s not clear he has similar negative baggage as Warren and Harris.

Bernie Sanders, in spite of his radical politics, does well in polls. If he is good enough at turning out sporadic voters who dislike both major parties, he might be the most electable candidate in the field. This would be in spite of the median voter theorem, his status as a sitting senator, his contentious status as an independent, and the fact that he comes from a small and very blue Democratic state.

The two most likely senators are the moderates, with solid political records. Amy Klobuchar has been remarkably effective at winning votes in Minnesota, and Michael Bennet has a very strong background on immigration issues. Both also come from medium-sized battleground states, which is a bonus.

Other experienced candidates

Of the remaining twelve candidates, only three have ever run for statewide office before; of those, only two have had any traction during the campaign. Steve Bullock is the only remaining governor in the race. Montana is a small state that votes mostly Republican but sometimes elects various Democrats to statewide office.

Bullock looks to be a likely electable candidate on the basis of those fundamentals. He might also be the most conservative candidate still on the field. Since nobody in the field is to the right of the national political median, this constructs an argument for his electability even as it makes him unappealing to progressive Democrats at the same time.

The other candidate is Beto O’Rourke, who has been frequently compared to Obama and RFK (by his detractors as well as his fans). Beto has explicitly reached out to both the moderate and progressive wings of the party (as well as reaching out to voters outside of the party), positioning himself as a liberal near the center of the Democratic Party.

Head to head polls of Beto are strong but scattered. He could realistically bring Texas’s 38 electoral votes into play; his losing bid for the Ted Cruz’s Senate seat was impressively close, and Trump is less popular than Cruz in Texas. He may be among the most radical in the field on gun control, but polling shows stronger support for a mandatory AR-15 buyback than for banning private health insurance or decriminalizing illegal border crossings, so this is probably not hurting his chances at winning a presidential election.

The less experienced candidates

Eight of the remaining ten “major” candidates have never even run for statewide office before. In 2010, Joe Sestak ran for senator (doing well but still losing) and Pete Buttigieg ran for state treasurer (doing badly and losing). (Note: A previous version of this article erroneously stated that none of these candidates had run for statewide office before.)

Let’s step back and explore the magnitude of the difference: Presidential elections involve over 100 million votes. None of the remaining contenders have ever been in an election where more than half a million votes were cast. The Democratic primary is their first attempt to appeal to a larger audience.

Five of those candidates have held office in the federal government, four as representatives and one in Obama’s cabinet. Most of this group probably are worth examining and considering in terms of electability. Two (Gabbard, Sestak) are veterans; two (Ryan, Delaney) are explicitly running as moderates; two (Sestak, Ryan) come from likely battleground states and could have a significant home state advantage.

Julian Castro’s candidacy has been higher profile than the rest in this group, allowing some evaluation of his appeal to the general population. He has positioned himself as a radical, attacking the Obama administration and calling for the decriminalization of border crossings. On that basis, I suspect he is not electable.

The other five candidates come from outside of the normal field of political backgrounds for presidential candidates, making them total wildcard candidates.

We can identify apparent weaknesses, such as Marianne Williamson’s unfavorable ratings or Pete Buttigieg’s poor head-to-head polling, but it’s hard to evaluate their potential strengths.

Personally, I think that Andrew Yang is the most electable-looking wildcard candidate. He has big bold ideas, and his fan base reaches outside of the Democratic party. He’s embraced unifying rhetoric reaching out to voters outside of the Democratic party — like Beto O’Rourke, Joe Biden, and the moderates. Even if he is arguably the most radical candidate in the entire field, he is not the most divisive.

Recap and review

Between head to head polling, favorability numbers, electoral history, stances on major issues, and the historical record, it’s clear why folk wisdom positions Joe Biden as the electable candidate. First, by the numbers, he is the most obviously electable candidate. Second, since blue media appears to favor less electable candidates, he’s not often compared to the most electable alternative candidates.

The four major likely alternatives as electable candidates are Amy Klobuchar, Beto O’Rourke, Michael Bennet, and Steve Bullock. Most of these candidates are firmly in the moderate wing of the party, with the notable exception of Beto, who doesn’t fit neatly in either the moderate wing or progressive wing of the party. They’ve also been tested in statewide elections and performed better than a typical Democratic candidate; all four of them also have a reasonable chance of carrying their home state when less electable Democrats might lose it.

There many other possible candidates who seem likely to be electable, but are largely untested; in particular, I would list Cory Booker, Andrew Yang, Tulsi Gabbard, Tim Ryan, Joe Sestak,and John Delaney as possibilities that the general electorate simply don’t know enough about yet. Even the most moderate of these candidates have progressive agendas that call for significant forward movement in this country on many Democratic issues; the conservative wing of the party is almost dead.

Many of these candidates are not being covered as much — or as nicely — by blue media. In the case of Beto O’Rourke, this involved a jarring sudden reversal of the tone of coverage; in the case of Andrew Yang, it has involved conspicuous omissions and refusing to give him the same air time as other candidates.

It’s unfortunate, but just as in the 2016 cycle, it feels like blue media outlets are more interested in trying to shape public opinion than reporting objectively on the candidates. If Democrats want to maximize the odds that they win the presidency and gain ground in Congress and state governments in 2020, it should be important to pick a good standard-bearer.

Change log

Updated on October 18th to include additional head to head polling. Corrected November 3rd and November 21st; with the additional information of a statewide race from Joe Sestak and Pete Buttigieg, the table has been updated. Honestly, I’m not sure why the media never went through a cycle of paying attention to Joe Sestak, he looks pretty good to me other than the fact that he doesn’t seem to be getting anywhere in the Democratic horse race.