Is the House of Representatives too small?

The reason 435 isn’t enough and the story of how it got that way

At present, the average population of each congressional district in the United States is 770,000. With the notable exception of India, every other nation with anything resembling a functional democracy has at least one legislative assembly with smaller average constituencies. Even the supranational European Parliament averages a ratio of only 630,000 constituents per member.

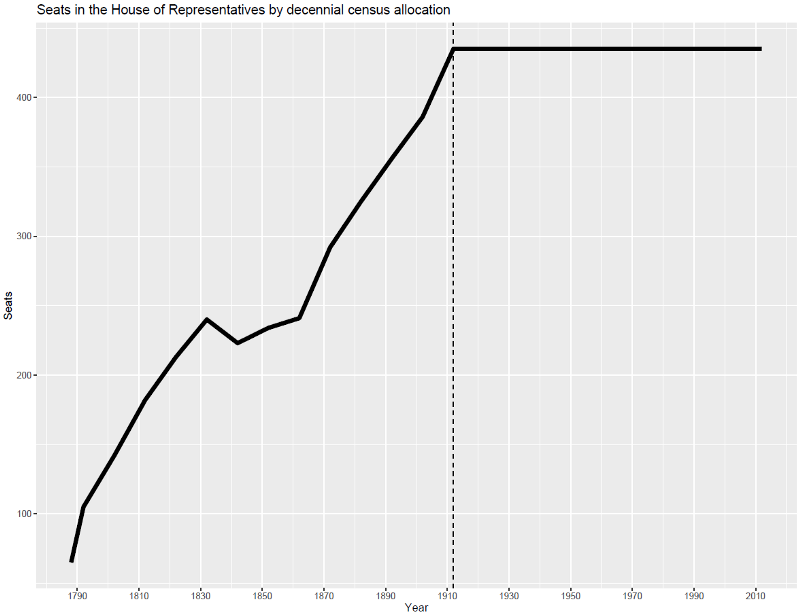

The size of the United States House of Representatives increased fairly regularly from 1788 to 1912, and then suddenly stopped growing. This has probably reduced the quality of representative government afforded to American citizens.

What’s wrong with a small House?

A too-small legislature is less responsive to the needs of citizens. A too-large legislature has trouble operating and passing legislation. But why is the cube root ideal?

The cube root law began as an observational law: Most of the functional legislative bodies found in the world are approximately the size of the cube root of the population. However, in support of this observation, there are very simple and very clear models for why the cube root of the population is a natural lower limit for an effective representative body where each representative has a similarly-sized group of constituents.

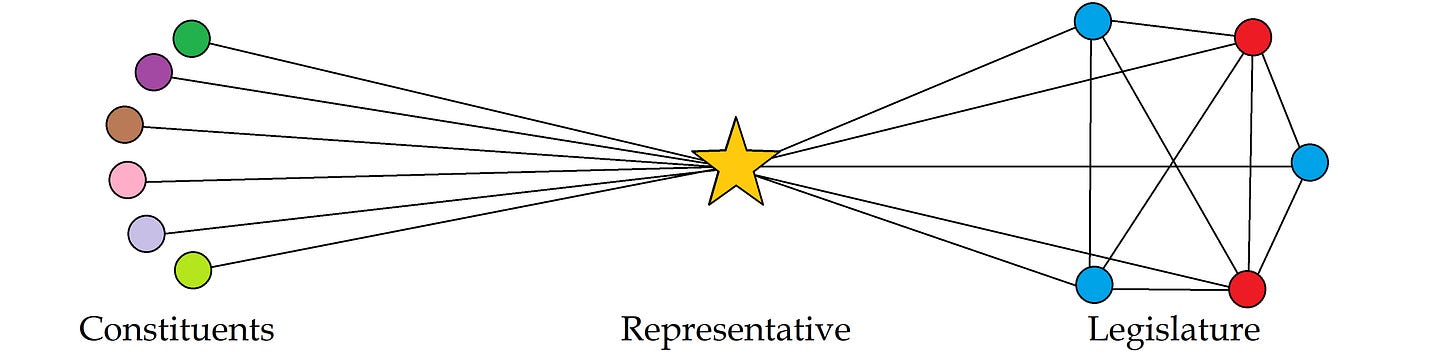

How easy is it for a citizen to bring an issue to the attention of the national legislature and to get the legislature to pass a new law, amend an existing law, or strike down an old law? The first step is that the citizen has to get the attention of their legislator. The difficulty of this is directly proportionate to the number of other constituents their representative has; that is to say, the difficulty is N.

Once the constituent manages to convince their representative to take action, that representative then needs to convince the legislature to act. But for each of the n-1 other legislators, the representative is competing for attention with n-2 other legislators. So the difficulty here is (n-1)*(n-2) - or roughly the square of the number of members of the legislature. There are various potential modifications that could be made (e.g., needing only 50% of members, but needing back-and-forth communication to negotiate).

In general, the sum of these two components is minimized if N and (n-1)*(n-2) are close to equal - when the number of constituents per representative is a little less the square of the size of the legislature, which happens if the size of the legislature is roughly the cube root of the total population. This is the most basic model, but very few refined versions of this model suggest better representation from having constituencies larger than the cube root of the population.

In general, the core pattern is that constituent-representative communications difficulty scales up linearly, while the legislature’s operational complexity scales at most with the square of the size of the legislature.

How did we get here?

This is a recent, if gradual, development. The Constitution limits the size of the House to no more than 1 representative per 30,000 residents. The earliest allocations set the number of members of the House not much higher than this. At the time the Bill of Rights was written, many thought that as the country expanded, the number of representatives should eventually be about 1 per 50,000 or 60,000 people.

From 1788 to 1912, the House of Representatives expanded regularly. Initially, the size of the House expanded quickly; but from 1822 to 1912, the size of the House, like that of many national assemblies, grew. The main driving factors were the addition of new states and the fact that the House delegations of existing states didn’t want to lose their seats. Most states avoided losing representatives most of the time.

And then … there was the 1920 Census.

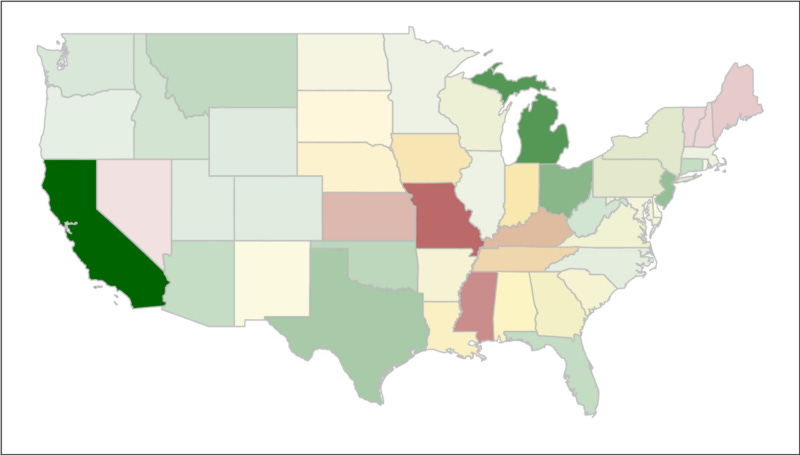

The 1920 Census was controversial for several reasons. The Census Bureau changed the effective date of the Census to January 1st. This meant that seasonal workers were counted as living in their winter homes in towns and cities, rather than in the rural farms they worked and lived in during the summers.

Partly due to this artifact of counting, the populations of cities grew massively in this period. Detroit’s population doubled; Los Angeles’s growth rate was only a little bit less than that. Older cities weren’t left out; New York added almost a million people and Chicago over half a million. Some of this increase was due to industrialization and changing patterns of immigration; urbanization was a long term trend, driven by increased mechanization of agriculture and growing industrialization in cities.

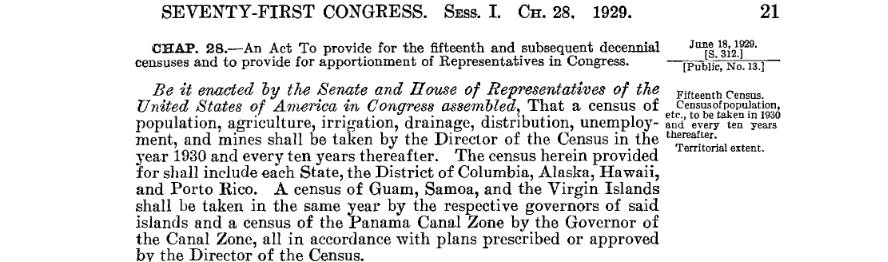

If the size of the House stayed the same, half of all states would lose seats due to reallocation. Enough politicians refused to recognize the results of the 1920 Census as legitimate that no reallocation of Congress happened using the 1920 Census data. Nobody wanted a repeat of this fight. So, in advance of the 1930 Census, the 71st Congress passed a permanent apportionment act, fixing the size of the House at 435:

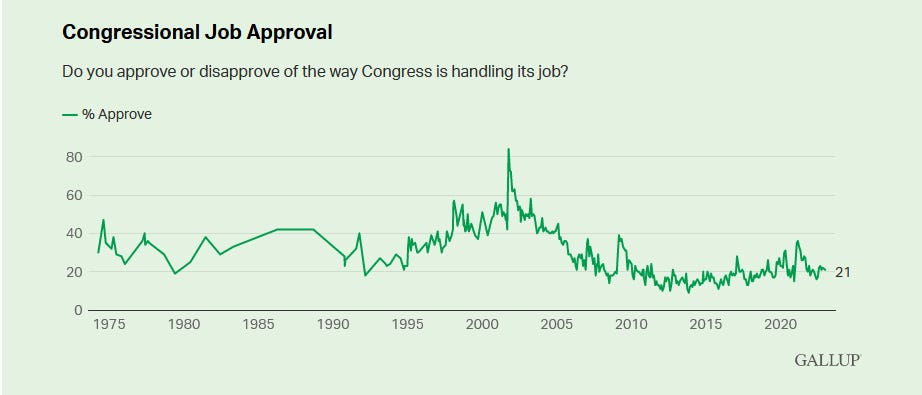

Ever since then, the size of the House of Representatives has been fixed at 435, in spite of the fact that the population has nearly quadrupled since then. Polling data on the subject doesn’t extend backwards to 1900, but what we have shows deep dissatisfaction with Congress and hints at a long-term trend of ever-lower levels of satisfaction with Congress.

In addition to the low satisfaction ratings, we also see increased levels of clear partisan polarization, gridlock, and other forms of malfunction in Congress that show that Congress is becoming less representative of the population. Congress is failing to act in many cases where a large majority of the population wants action. Something isn’t working; and the House being too small is one possible cause of failure.