As I have previously noted, there are numerous alarming signs that the quality of political polling has declined substantially. For the last several months, it has been my contention that poll-based forecasts of the election are likely to be lower quality than historical forecasts of the election based on the previous two elections.

That is not to say that presidential elections can usually be predicted well by the previous two elections. In fact, historical models of elections are generally bad, as the parties periodically realign themselves substantially. Even given that Trump was on the previous two Republican tickets, I do not expect the historical model to perform exceptionally well; instead, I expect that polling-based models have limited accuracy.

I’m putting this post out before the election to preregister my assessment of the quality of current polling. Because the main wild card in this election is the fact that Joe Biden stepped away from the nomination, the historical model also serves as a benchmark for the Democratic decision to run Kamala Harris.

The simplest models: Averages and trends

The simplest way to predict the result of any event is to guess that it will be roughly the same as the previous time. The next simplest way to predict events is by guessing that it follows a trend that changes over time, and forecast the trend based on two or more of the previous instances of that event. Usually, the best guess is somewhere between the trendline prediction and a simple average, but usually any prediction falling between an average and a linear trend is somewhat plausible a priori.

What I will do in this basic historical model is predict the results of the current presidential election based on the previous two presidential elections. This is necessarily a very simple model, with two steps: First, project the current vote for a party based on the previous election. Second, adjust the estimate for overall turnout.1

With only two previous points used for prediction, both trend and average models are just weighted sums of both previous points. For a trend model, this is a weight of 150% of the previous cycle and -50% of the cycle before that; for an average model, this is a weight of 50% for each of the two cycles.

In objective terms, both of these models are terrible at predicting historical election results, even after throwing out all elections with more than two major candidates, the Reconstruction era, and the largely unprecedented 1932 election. Out of n=563 statewide elections for president in the 12 most ordinary-looking presidential elections, fewer than a third have results that fall between the predictions of the average model and the trend model.

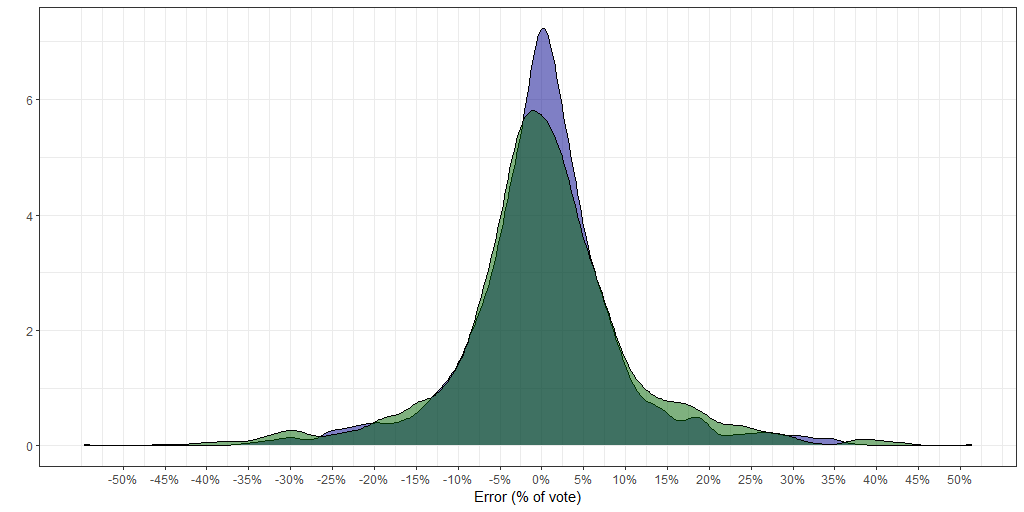

This is, I will reiterate, a genuinely bad model. Even after focusing on the 12 most ordinary presidential elections in American history, the root mean square error of the trend model is 9.2% of the electorate, while the root mean square error of the average model is 7.8% of the electorate. A weighted average (75%-25%) has slightly better performance, with an error of 7.3% of the electorate.2

Predicting 2024: Illustrating the models

While this isn’t true for every state, the fact that Joe Biden performed considerably better in 2020 than Hillary Clinton did in 2016 means that the trend model predicts better Democratic results, while the average model predicts worse Democratic results.3 Between these is a natural parameterized range of linear historical models.

Reversion to the mean predicts an extremely narrow electoral victory for Donald Trump with 271 electoral votes and a minority of the vote; the trend model predicts a 303 electoral vote Kamala Harris victory similar to Biden’s 2020 map with a stronger popular vote margin.4 The most realistic weighted average model predicts a 276 electoral vote victory for Kamala Harris.

Judging the prediction models

For the purpose of calculating error in a prediction model, I will look at the root mean square error of the model’s central predictions of the popular vote in each state. My baseline prediction is that at least one model in my specified range of historical models will outperform some poll-based models.

Based only on the historical validation, I have selected the 75-25 weighted average model as most likely. If this model, specifically, outperforms most poll-based models, I can reasonably claim I’ve predicted the election better than the polls.

If none of the specified range of historical models outperform any of the poll-based models, then I clearly owe pollsters a collective apology for managing to overcome the extremely difficult polling environment with modern response rates.

Judging the choice of candidates

If Kamala Harris performs better than the historical range of models in a state, this would be evidence in favor of the switch having been a true game-changer. Similarly, Kamala Harris performing worse than the historical range of models in a state would be evidence that she was a poor choice of standard-bearer.

Not entirely independently, Trump’s performance can also be evaluated by the same benchmark. In 2020, Trump performed between the average and trend of the 2012-2016 cycles in twenty-six states, higher than the historical average of around one third of all states.5 My personal expectation is that as a third-time candidate, his performance will likely be between the average and trend of the 2016-2020 cycles in more than twenty-six states this time.

Whether or not the polls prove incorrect, I will follow up after the election by using the historical “previous two” election model as a method of estimating the strength of 2024’s presidential candidates as well as others over the years… so stay tuned.

This last step is necessary because elections sometimes involve large changes in absolute turnout numbers, in many cases due to rapid changes in the size of the eligible electorate.

By comparison, most polls have an expected error of less than 5% based on sample size… if one assumes that the respondents are a truly random sample of the population.

Donald Trump’s performance in both elections was approximately the same, although trends both up and down were visible at the state level.

Also, the trend model predicts negative votes for Donald Trump in Delaware, so it’s guaranteed to miss at least one state reasonably badly.

Interestingly, he overperformed in eighteen states and underperformed in six. The fact that this was not good enough highlights both how lucky Trump got in managing to win the Electoral College in 2016 given his overall level of popular support and how much more effective Democrats were in 2020 than in 2016 - the Biden campaign brought 2016’s third-party voters into the Democratic fold, at least temporarily.