Democrats lost the House because they won fewer votes

The bad takes will circulate for a while. Ignore them.

I’ve just read an article claiming that independent redistricting commissions cost the Democrats the House this cycle, and calling for Democrats to abolish independent redistricting commissions in states they control in order to carry out blatant partisan gerrymandering. I’m sure this article isn’t alone or isolated; I’ve been reading and hearing comments from loyal Democrats saying the same thing. This is wrong on several levels.

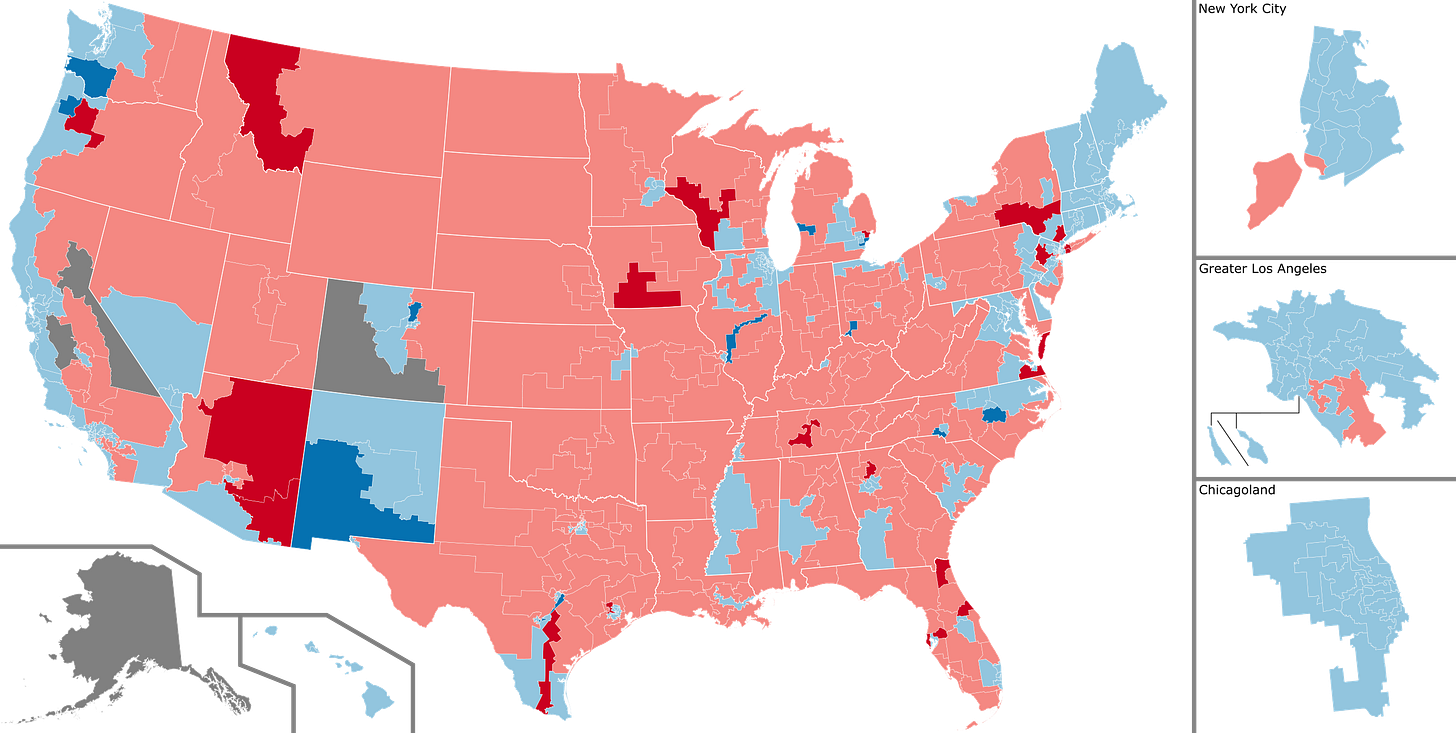

Republicans won more votes than Democrats in 2022, as frequently happens in midterm elections when a Democratic president is in the White House. Because their House candidates won more votes, they deserve to have more seats. Gerrymandering is erosive and corrosive, and it remains important for reformers to fight gerrymandering as much as they can.

The 2022 results summarized

Right now, it looks like Democrats won 3.5 million fewer votes nationally. This margin is likely to shrink a bit as California and New York finish counting; these are Democratic strongholds that are notoriously slow at counting. Based on projected turnout and current trends in results, California and New York may narrow the margin to about 2.5 million votes. If we look only at votes cast for the two parties, House Republicans probably won by a margin of close to 3 percentage points.

While final results are not yet in for all House seats, it seems very likely that Republicans will win 221 or 222 seats while Democrats will win 214 or 213 seats, an unusually narrow majority by the standards of the House of Representatives.

The best news of the election is that candidates who defended the democratic processes of the 2020 election (such as Georgia’s Republican candidate for Secretary of State) generally did much better than candidates who attacked those processes (such as Arizona’s Republican candidate for Secretary of State).

What would happen if there was no gerrymandering?

Based on the mathematics used in calculating the efficiency gap, we would expect a victory margin of 3% in the national vote for the House of Representatives to lead to a 230-205 majority in the absence of any natural geographic effects or gerrymandering. For example, in the 2004 House elections, Republicans won by a 2.6% margin and gained a 232-202 majority.

If seats in the House were assigned perfectly proportionate to the parties that voters voted for in the general election, Republicans would have 221 seats, the Democrats would have 207 seats, and 8 seats would need to be divided between minor parties. With proportional representation and a minimum party threshold of 5%, Republicans would have somewhere around a 224-211 seat majority.

In other words, right now, the results for the House of Representatives are strongly proportional. Republicans won more votes and more seats. If anything, Democrats have retained more seats than expected, albeit not many more. This is an ordinary result.

But there was gerrymandering, right?

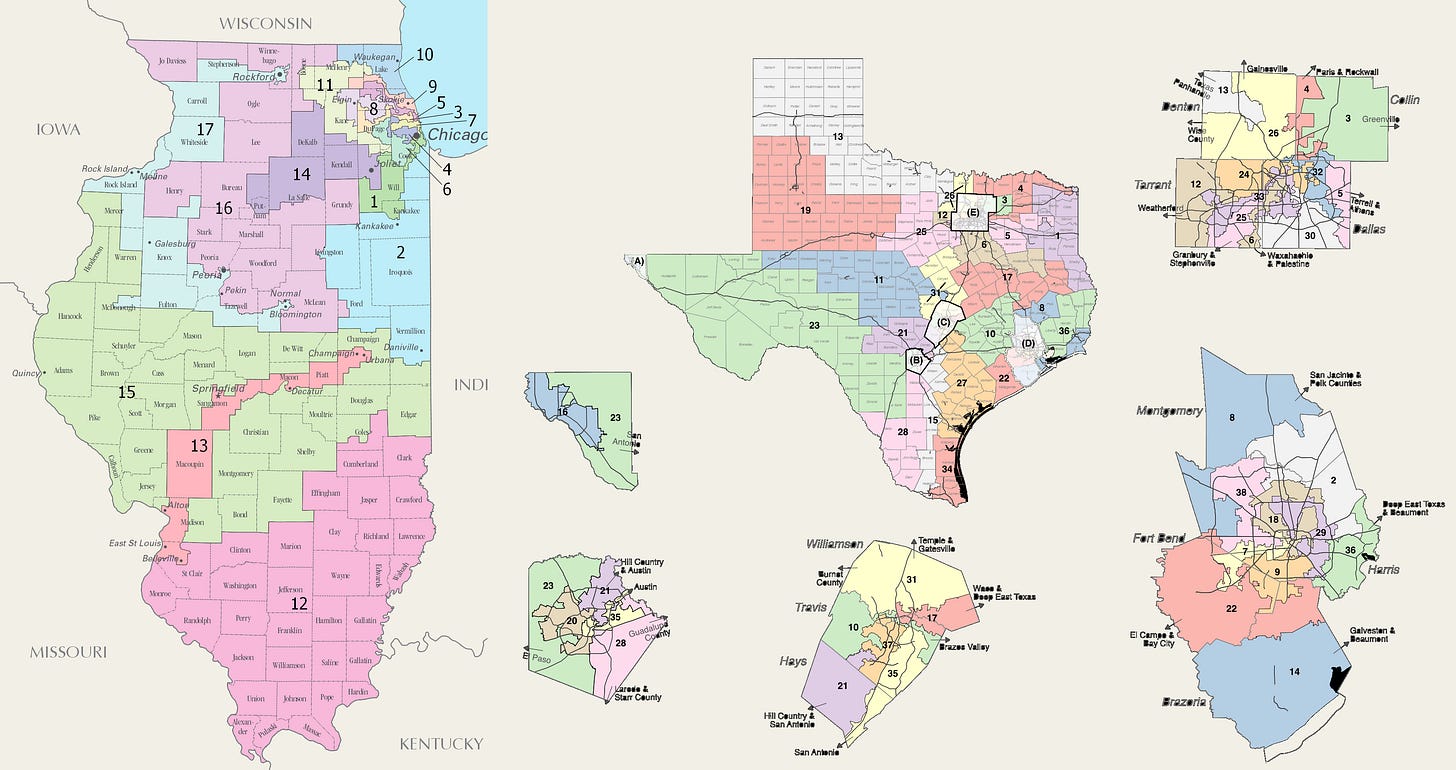

Yes. The 2020 redistricting cycle involved blatant partisan gerrymandering as well as an uptick in action by redistricting commissions and state courts. New York, in particular, got to experience the excitement of all three potential map-making bodies.

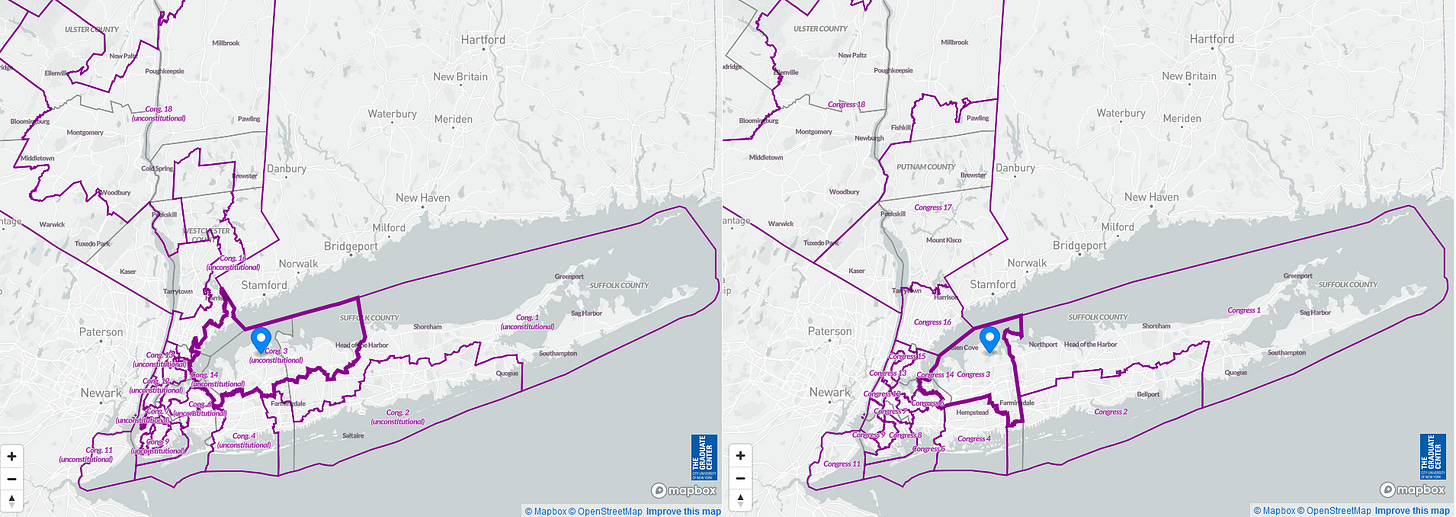

One of the major events that happened in the 2020 redistricting process was that the State of New York had a special bipartisan commission appointed by the state legislature, with an even number of members. (This is unlike California’s process, which puts partisan involvement of the legislature at a slightly greater remove.) As might be expected from a bipartisan commission directly appointed by the legislature, the commission deadlocked.

This put the drawing of New York’s congressional districts in the hands of the New York state legislature, which promptly drew an egregious partisan gerrymander. Among numerous other obvious problems, the map included a district that was only “contiguous” by including part of Long Island Sound - an uninhabited stretch of water. The courts threw this map out and substituted a fair map.

New York Democrats did badly in the midterms. The lesson to take from this is not that New York Democrats needed to do a better job at gerrymandering. It is, instead, that New York needs to improve its redistricting commission selection process in order to produce a more independent group of commissioners who won’t deadlock on partisan lines.

Blatant partisan gerrymanders were left in place in numerous other states, notably including Texas and Illinois. Bipartisan gerrymandering makes the House results less responsive to shifts in public opinion, cementing incumbents in place on both sides of the aisle.

The main effects of these gerrymandering efforts on both sides were shielding incumbents from accountability, reducing the number of districts that were competitive, and driving down voter turnout and enthusiasm across the country. The 2020 redistricting cycle was not like the 2010 redistricting cycle, where one party was in a position to gerrymander much more effectively. The House of the 118th Congress that was just elected will feature better partisan proportionality than the House of the 113th Congress did.

If you care about the legitimacy and integrity of elections more than temporary partisan advantages, you should continue to support independent redistricting commissions. States that do not have independent commissions should adopt them; states that have commissions that have proven to be more partisan than independent, such as New York’s deadlocked commission, should be improved rather than discarded. These reforms have usually been opposed by many partisan loyalists on both sides, including in the notable case of California’s highly successful reforms that went into place in the 2010 redistricting cycle.

Caveats about the House popular vote

One small caveat is that measuring the national popular vote by House results is distorted by differential turnout and by the fact that not all parties run in all districts. Some candidates ran unopposed, some were only opposed by a third party candidate, and some were opposed by members of their own party. Trying to add together ranked choice ballots from states like Maine and Alaska with plurality ballots from other states is also difficult, because the reported totals have somewhat different meanings.

For example, Republican John Joyce of Pennsylvania’s 13th District ran unopposed. Republican Dusty Johnson of South Dakota’s only district faced only by a Libertarian candidate, Collin Duprel. Voters who voted Democratic in other races on the ballot couldn’t vote for Democratic candidates in those races. Meanwhile, in California, Democrats Anna Eshoo and Rishi Kumar competed in California’s 16th District, racking up votes for Democrats on both sides.

In general, this distortion of the national popular vote for the House tends not to be especially significant. Most seats feature at least one candidate from each of the two major parties. There are non-competitive seats on both sides. Additionally, turnout in the races that feature only one major party tends to be lower than more competitive races, which reduces the impact of these races on the national partisan vote totals.