How should we end gerrymandering?

Inviting open comment on an algorithmic approach

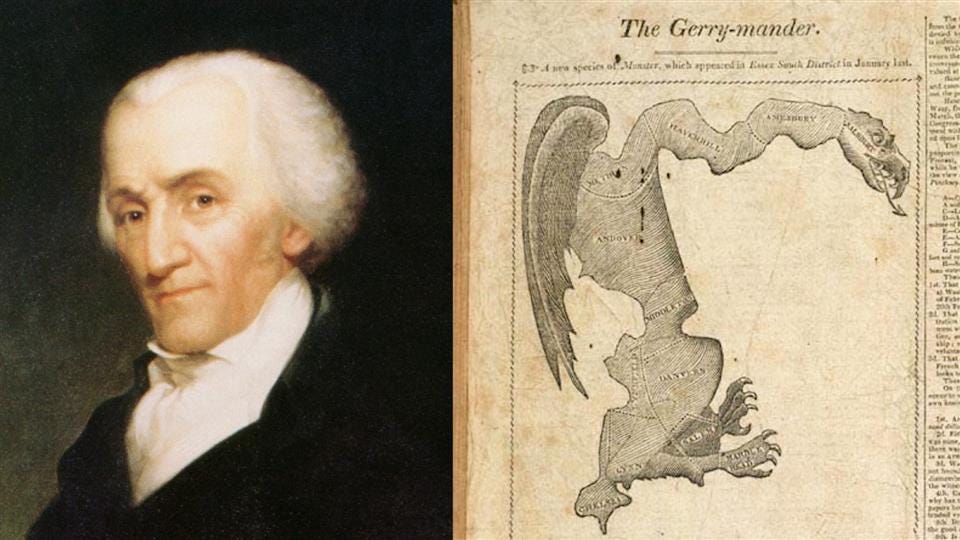

Gerrymandering, the practice of drawing the boundaries of electoral districts in order to gain a political advantage, is enjoying one of its perennial moments in the public eye. As I have discussed previously, this is a problem that the Founding Fathers did not anticipate, and which poses multiple difficulties for democracy.1

What I want to do today is to take the first steps in building a fair and transparent algorithmic approach to drawing districts. The goal is to provide a model for avoiding gerrymandering.2 This is slightly complicated by the contradictory legal standards surrounding racial gerrymandering, but I strongly believe that a facially neutral system is the best basis.3

Measuring district quality

The goal of the algorithm will be to approximate the following attributes:

Maximize contiguity between county and district boundaries.4

Minimize division of population centers.5

Maximize overall compactness of the district map.6

As a basic fact of geometry, given n districts, it should be possible to draw a map contains no more than n-k-1 instances of a partial district within a county, where k is the number of districts that can be drawn inside of the boundaries of a heavily populated county. Any iterative approach that draws one district at a time using whole counties and adds at most one partial county with each new district drawn will include at most n-1 cases where a partial district is within a county.

Since county lines generally do not vary much over time, are usually not redrawn arbitrarily, and usually serve as boundaries for election administration, county lines serve as a reasonable basis for an algorithmic approach. I will formalize an algorithm using county lines and the US Census’s subdivisions (census tracts, et cetera).

My previous approach

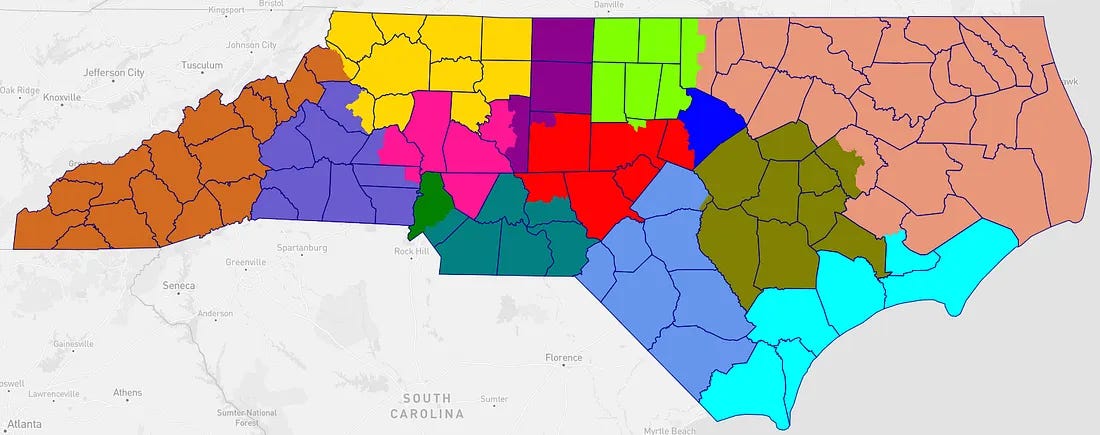

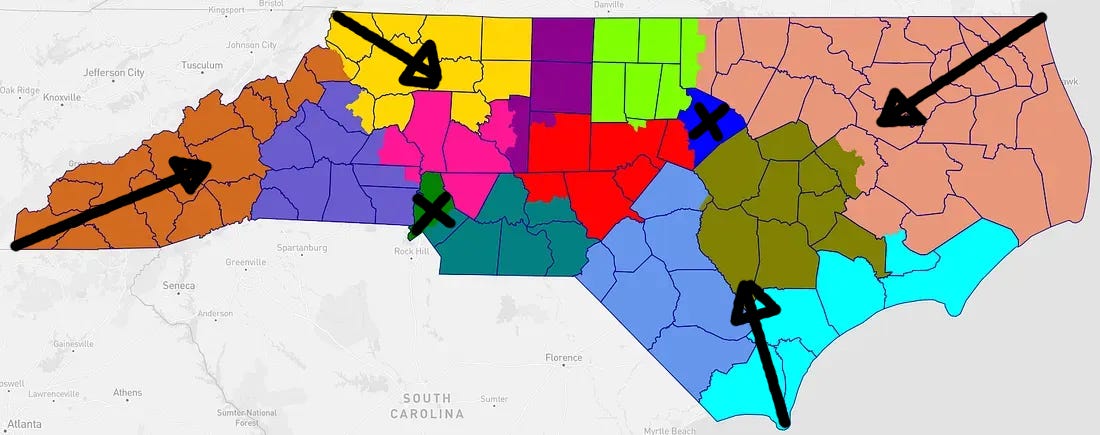

In order to provide a point of contrast during my discussion of the Rucho case, I gave an example of drawing districts for North Carolina that used the following steps:

Identify the n largest population counties as possible centers for districts.

From this pool, eliminate counties that are small enough to be potentially combined into a single district and adjacent to each other. This gave me the kernels for eight districts.

Identify natural regions of geography (Appalachia, coastline).

Fill in the gaps, trying not to split cities or counties unnecessarily.

This is not a very easy to formalize approach. The results were a perfectly fair map for use in comparisons to the real-life maps, but while the process was fairly mechanical, it is still difficult to formalize and may not work as well for different physical distributions of populations.

Outline of a proposed algorithm

So, I would propose the following process:

Identify all counties with populations large enough to contain at least one district and reserve within-county districts to those counties.

Select a new county to start a district with.

Add whole counties by shared boundary metrics until the population quota is met, then add a last partial county.

Repeat steps 2-3 until no unassigned counties remain.

Divide counties based on the same principle of minimum boundary length using census tracts.

Repeat step 4 with census blocks within census tracts.

States are divided into counties or county-like objects; counties are divided into census tracts; census tracts are divided into census blocks.7 Census data is freely available, and the census subdivisions are directly linked to the population data that serves as the basis for apportionment.

Properties and puzzlements

How do we pick a new county in Step 2? One choice would be to pick up with the partial county that we left off with in the previous cycle, which minimizes division of counties. Another choice is to look out… as in literally outward.

The key thing that made filling in my original NC map straightforward was the fact that after reserving districts within Wake and Mecklenburg that would not cross county lines, I essentially worked my way from the outside of the state inward. This was caused by my focus on physical geography, looking at the mountains and the coastline. Once I had finished the outermost four districts and two inner metropolitan districts, filling in gaps was straightforward.

The VRA problem

The Voting Rights Act has been interpreted as both forbidding and requiring a certain amount of racial gerrymandering in order to create majority-minority districts. Majority-minority districts also tend to be naturally “packed” districts that distort the overall partisan fairness of the map, an effect that was crucial in creating the Republican gerrymander advantage of the 2010 cycle that led to a rare example in 2012 of a party winning a majority of House seats without a plurality of the vote.

This is a complicated issue that cannot be solved easily or fairly by algorithm because there is no consistent objective standard that can resolve the difference between “good” and “bad” racial gerrymandering under the historical standards used to apply the VRA.

Not entirely coincidentally, it is thought likely that the Supreme Court will decide entirely against both “positive” and “negative” racial gerrymandering before the next redistricting cycle. This, in turn, means that algorithmic redistricting is likely to become practical even in states where natural compact districts will not include many majority-minority districts.

Call for commentary

So, what do you think? Please leave feedback and suggestions in the comments, and I will incorporate those in my discussion in my next article.

The majority in Rucho v. Common Cause claimed otherwise, but factually, this is based on a misunderstanding of the historical record. In modern terminology, the term “gerrymandering” is not used to refer to malapportionment, which was the primary method of drawing districts for political advantage prior to the writing of the US Constitution.

Broadly, districts that are drawn compactly and algorithmically without political considerations cannot be “gerrymandered” by any reasonable definition of the term. The problem is advance coordination.

Essentially, the Voting Rights Act has been read as both requiring and prohibiting racial gerrymandering in the form of minority-majority districts. There is no robust method for achieving proportionality of representation by a politically distinct minority in a single member district system that does not involve deliberate gerrymandering. The methods I outline above will lead to the election of minority candidates to the degree that those minorities control geographically coherent and compact communities and to the degree that districts are of sensible size.

I.e., minimize the number and severity of cases where a partial district may be found within a county.

Gerrymanders frequently take one of two form factors: A long “snake” or “tentacle” format, such as the original salamander-like “Gerry-mander,” or a radial pattern around a population center. The radial pattern emerges as an attempt to either dilute or amplify the power of a major population center.

Defining “compactness” is not trivial.

Counties or county-like subdivisions include parishes, independent cities, etc.