Ranked Choice Voting in the 2022 Elections

The good, the bad, and the ugly in voting reform news in the US midterms

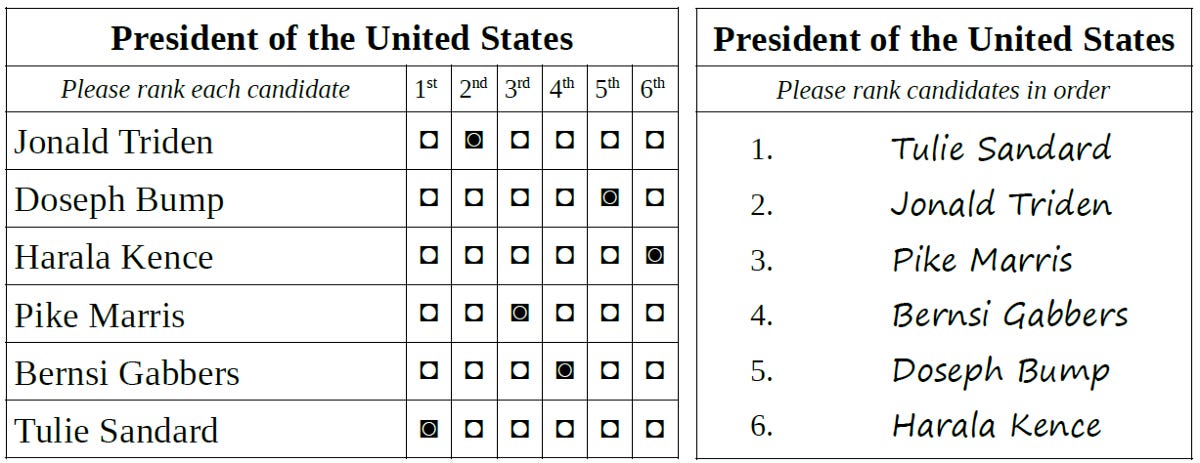

This cycle saw an increase in the use of the systems widely known in the United States as ranked choice voting (RCV). RCV was on the winning side of several referendums in this cycle, including one on the state level in Nevada and several at the municipal level. This is, in other words, another small step forwards for voting reform efforts, although Nevada will need to pass a second referendum in 2024 before the reform can take effect.

The good news is that RCV races went smoothly, undermining the criticisms offered from people who are simply generally opposed to voting reform. The bad news is that one of RCV’s well-known theoretical limitations was visible, in particular in the election for Alaska’s House seat. The ugly news is that voting reform advocates got into an internecine struggle in Seattle.

The good

In all six high-profile (statewide or federal) races this November that used RCV, the winner in the RCV process appeared to be the same candidate who would have won with the traditional system of partisan primaries followed by a plurality vote. This is normal and reassuring. The tallying process for both Alaska and Maine has gone uneventfully, although not quickly. The number of invalid ballots was not unusually high. A third state, Nevada, is now on track to adopt RCV for state and federal elections, and it has become increasingly hard for critics to say that RCV is a step backwards.

Instead, RCV made outcomes more certain and less susceptible to small shifts in ballots, as increased the final margin of victory. Races were less likely to be decided by errors (or fraud) in the counting process, lost or delayed mail-in ballots, or variations in turnout driven by essentially random things like inclement weather. The final victors could, in all five cases, claim a popular mandate backed by a majority of all voters (including voters whose ballots did not include secondary preferences). In other words, the process was mainly just less chaotic and helped the winners build a strong claim for a popular mandate.

This was visible in the cases of Senator Lisa Murkowski (R) of Alaska and Representative Jared Golden (D) of Maine’s 2nd district. Both won narrow pluralities in the first round of tabulation, but clear majorities in the final tabulation. In Murkowski’s case, her principal opponent was a fellow Republican, which is a situation that she faced without the benefit of RCV in 2010 and 2016. In spite of the fact that she has faced election four times, this year marks the first time that Murkowski has won a majority of the vote; her previous victories have been plurality victories in which she earned less than half the vote.

This didn’t happen because Murkowski has become more uniquely in tune with the desires of Alaskan voters. This happened because Alaskans were allowed to express themselves at the ballot box more clearly. A significant number were willing to support Murkowski even if she wasn’t their top choice.

The bad

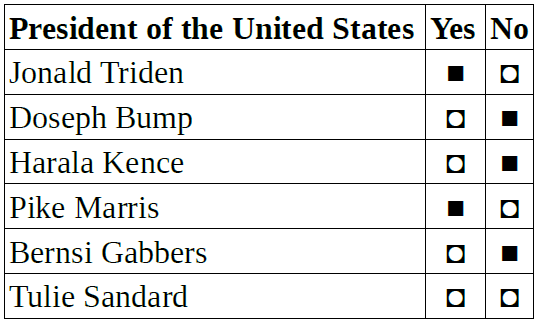

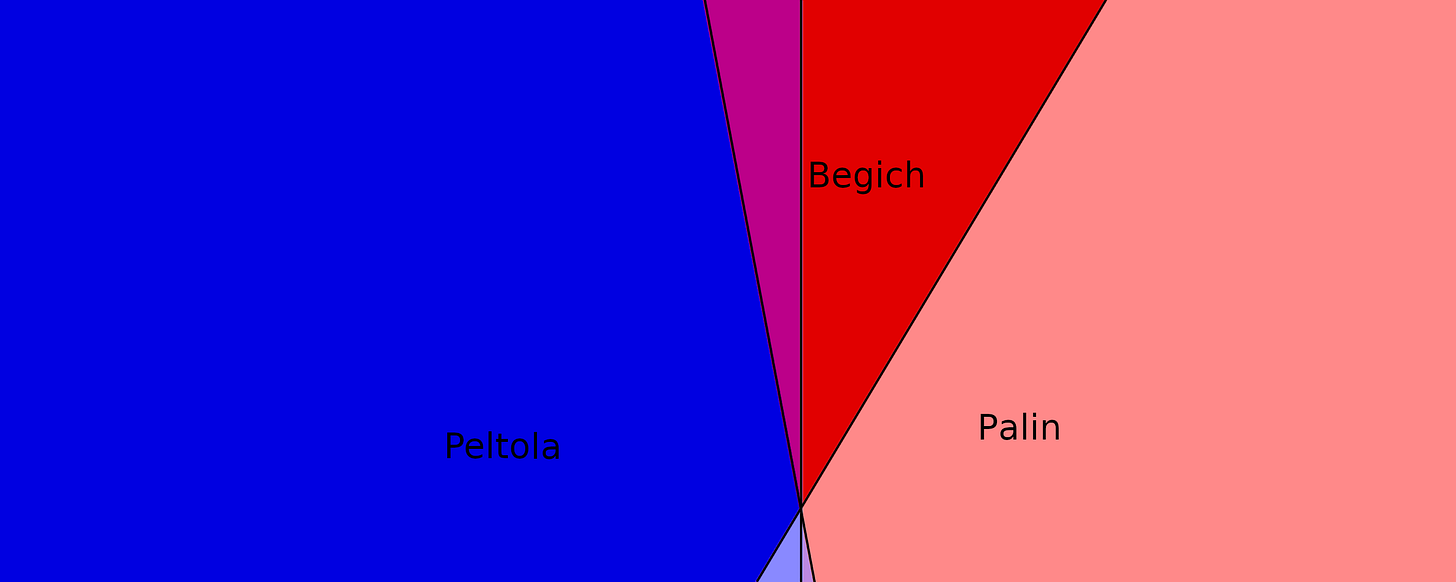

The second-place finisher for Alaska’s seat in the House of Representatives was Republican Sarah Palin, losing to Democrat Mary Peltola. However, Palin was not the most popular Republican candidate on the ballot. The other Republican candidate on the ballot, Nick Begich III, was more popular: Both polling data and ballot data indicate that a majority of Alaskan voters preferred Begich to Palin.

Nevertheless, the RCV process eliminated Begich before Palin, both in the special election in August and in the general election in November. Most voters who preferred Begich to Palin had Peltola as their first choice, while most voters who preferred Begich to Peltola had Palin as their first choice.

It’s worth underlining that this particular type of result is very normal in elections across the United States. Begich likely would have placed third in a plurality vote, and in a primary election using a plurality vote leading to a two-candidate election, the order in which candidates were eliminated would have most likely been the same: Begich getting eliminated earlier, and then Palin losing to Peltola in the general election. In a three-way plurality contest, Begich would have also likely placed third.

Republicans upset with the result of a Democrat representing Alaska in the House should not blame Alaska’s voting system reforms. They should instead blame Palin for choosing to run when she was not the strongest Republican candidate available, or start to look into possible voting system reforms that consider voters’ secondary preferences earlier in the process. It is likely Begich would have placed higher than Palin in an approval vote, a STAR vote, or a Borda count.

The ugly

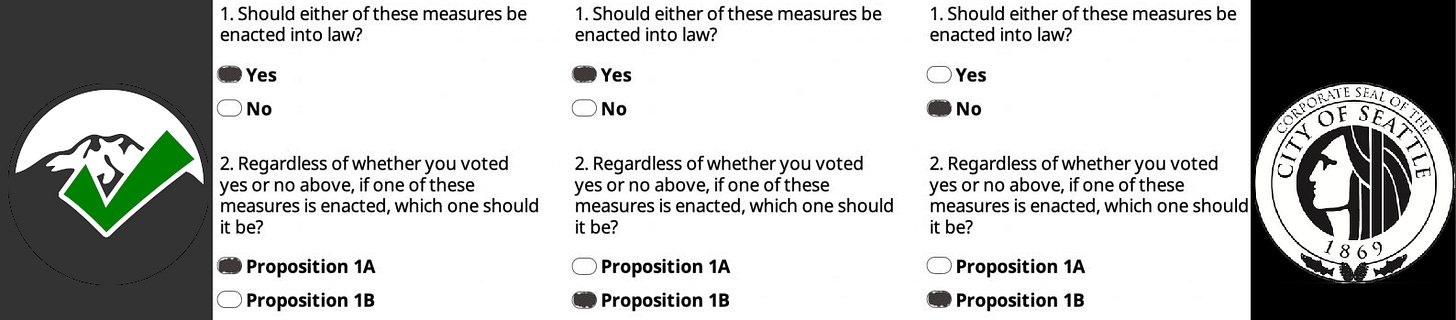

Voting reform activists pushed for Seattle to adopt approval voting in its top-two municipal primary elections. Early surveys carried out by approval voting advocates indicated this proposed reform was likely to pass, and the Seattle Approves group was able to meet the signature-gathering requirements to put this reform question on the ballot. Prospects for reform looked good; but what happened next got ugly.

From what I’ve been able to glean from reading news and reports at a distance, what happened next was that incumbents on the city council got nervous about the possibility of losing their next re-election campaign and tried their best to prevent voting reform.

The strategy they chose was to muddy the waters by turning a simple proposed ballot question into a more complex ballot question that introduced more uncertainty and confusion: Should voters change the existing method? If so, should primary elections be changed to use approval voting or RCV? The city council’s decision to modify the simple ballot question proposed and supported by a legally sufficient number of citizens was a decision to undermine the democratic process of the initiative system.

This strategy nearly succeeded. Both sets of voting reform advocates attacked the other reform alternative. With voters less certain about which reform would actually result from a “yes” vote and being fed a stream of negative rhetoric about both possible reforms, the first part of the ballot question barely passed with a margin of about 6,000 votes out of over 300,000 ballots. (RCV won the second ballot question by a large margin.)

Recap

Every election in which reforms win on the ballot and jurisdictions using voting reforms don’t see unintended backfires of the new system is a step forward for voting reform. This was true in this cycle: First, all the prominent RCV elections went smoothly; and second, the only RCV result out of those most prominent races that could reasonably be considered sub-optimal simply reproduced the existing behavior of the pre-reform system.

The ugliest news of the cycle was that opponents of voting reform were able to draw competing reform groups into an internecine struggle as part of a nearly-successful effort to block reform. This gambit, which involved blatantly undermining the initiative process, nearly succeeded at blocking reform entirely.