It’s been over a year since the Supreme Court banned racial affirmative action in Students for Fair Admission v. Harvard (2023). The vast majority of elite universities within the United States pursued aggressive affirmative action policies for a period of over half a century, a practice affirmed with limits in Regents v. Bakke (1978).

While one of the last exceptions to anti-discrimination laws was closed in the SFFA v. Harvard case, it is difficult to prove and prosecute discrimination, and those who believe that affirmative action is productive will continue to do so for some time in defiance of the ruling.1 Neither opponents nor proponents believe that affirmative action will end short of legal force, even as it becomes clear that the ideological frameworks used to justify a system of perpetual affirmative action create discord and division.2

Yet when affirmative action began, it was nearly universally described as a temporary measure by proponents - a one-time push to overcome decades of discrimination. After almost sixty years of affirmative action policy, it’s time to admit that affirmative action failed to accomplish its mission and ask why it failed.

Enough time has passed to declare failure

The Supreme Court that decided Bakke was one that was not personally familiar with affirmative action. The Supreme Court that decided SFFA v. Harvard was a court that could not remember life before affirmative action. The oldest justice was Clarence Thomas, an African-American justice who voted against affirmative action. When Clarence Thomas was admitted to Yale Law School in 1971, the Ivy League school was operating under an aggressive affirmative action program with a target quota of 10% of the law school’s entering class.

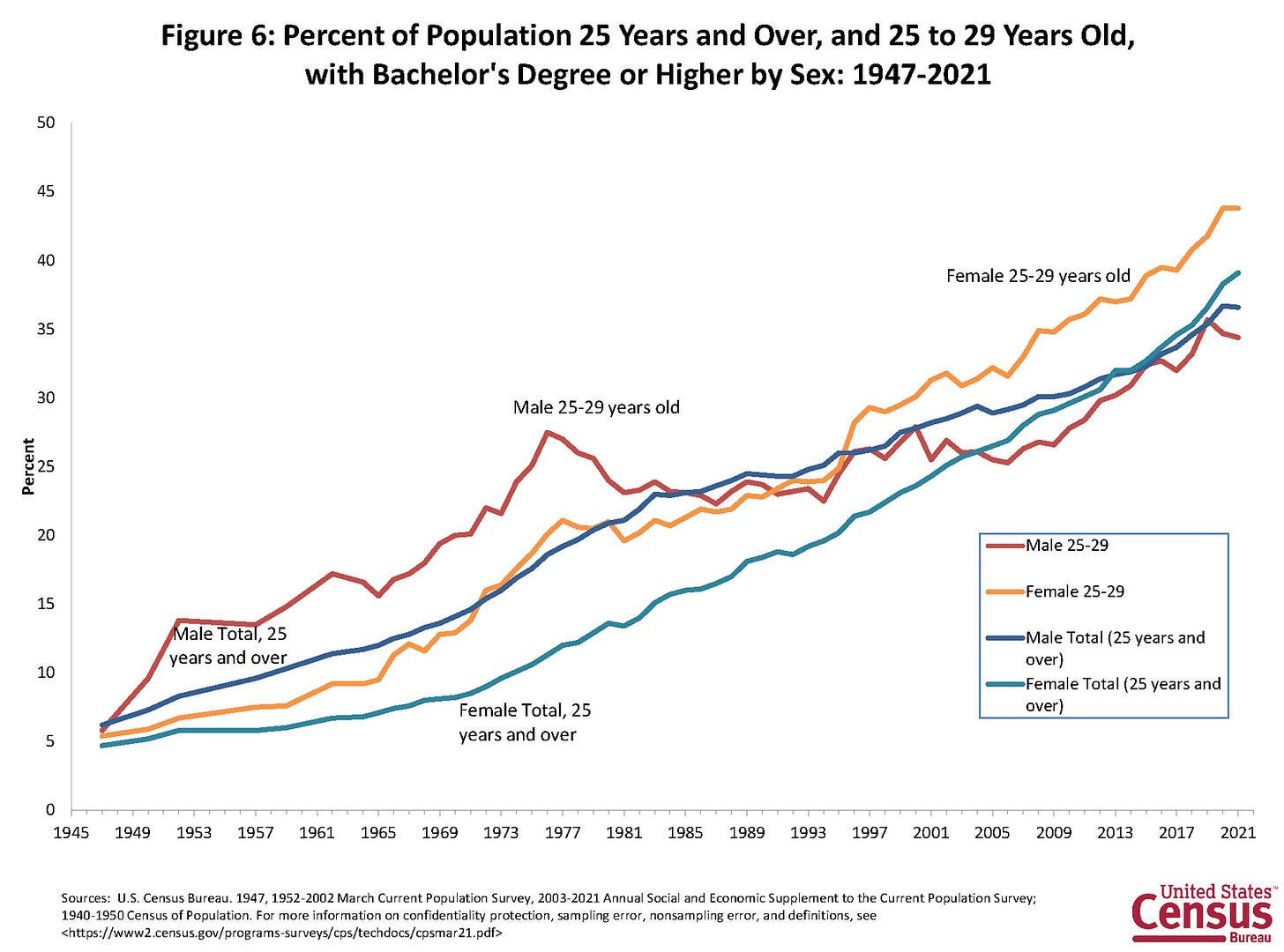

Enormous changes have taken place both in the workforce and within higher education, including the reversal of the gender education gap and the elimination of gender discrimination in pay.3 Similar changes have not emerged in the domain of race. While individual African-Americans have broken through to the highest levels of the elite,4 population-level gaps in income, wealth, and educational attainment remain very substantial, with few signs of overall progress in the last two generations.5

In fact, progress on racial income gaps, wealth gaps, and educational performance gaps between white and black Americans has been slower than would have been expected simply by the removal of discriminatory barriers. Since racial affirmative action was justified as a method of remedying recent historic discrimination against African-Americans under Jim Crow law, the failure to close the gaps between white and black Americans is a failure of affirmative action to accomplish its mission.6

Meritocracy works

As with many psychological and social phenomena, at most half the variation in socioeconomic status in the United States appears to be inherited from parents.7 A simple model of the impact of the removal of discrimination would predict an exponential decay in the impact of historical discrimination on each successive generation, with around 90% of the impact being erased by the third generation. This may seem slow, but we are now looking at the third generation of affirmative action recipients and have not seen anywhere near this kind of progress.

Historically, this crudely corresponds to what we see in immigrant communities.8 First-generation immigrants from non-English-speaknig countries face real barriers to integration; second-generation immigrants are fluent in both the English language and American culture; and the large majority of third-generation immigrants are difficult to distinguish from “old stock” Americans outside of holidays and family reunions. Very little scholarly work even attempts to use the concept of “third-generation immigrant.”

Even during periods where de jure discrimination was openly practiced, rigorously meritocratic processes coincided with significant socioeconomic progress by minority communities. The most significant closure of the gap between black and white wealth and income (circa 1870-1910) coincided with the presence of an integrated and strictly merit-based federal civil service system (1883-1913).9

Similarly, the first rise in standardized college admissions exams circa 1901-1921 offered Jewish-Americans chance to break into traditionally WASP-dominated elite social circles via Ivy League education.10 Even a small amount of strict meritocracy can be very effective at remedying the impact of of discrimination, particularly against a minority group. Why? To answer this, I’ll turn to game theory.

Discrimination is an anti-coordination game

One of the many ways in which companies compete with one another in a free market is in hiring. This extends naturally to college admissions, awarding of grants, and other settings in which affirmative action has been utilized.

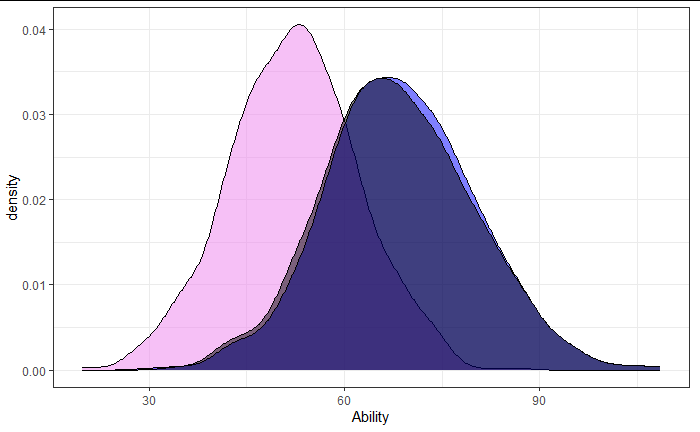

For the sake of simplicity in modeling, I’ll talk about an example with a single finite hiring pool of candidates that vary in a single dimension of quality, and two companies. The first company is large, well-resourced, and acts first.11 Candidates come from two groups with identical distributions of ability.

Let’s say that the first company engages in discrimination, but is also able to imperfectly observe ability. They hire what they believe to be the best members of Group A, while ignoring candidates from Group B regardless of how well they interview.12

It is now Company 2’s turn to hire. What does the hiring pool look like? Well, it includes a lot of high-quality members of Group B that were discriminated against by Company 1, and the members of Group A still in the hiring pool tend to be lower-quality, since this includes the candidates rejected by Company 1 for a poor interview score.

Consider three strategies for Company 2:

Company 2 also discriminates in favor of Group A.

Company 2 hires on merit (default strategy).

Company 2 discriminates in favor of Group B.

For the three extremal strategies, the distribution of hired candidate abilities looks like this:

If Company 2 discriminates in favor of Group A just like Company 1, the quality of their hires suffers substantially.

If Company 2 discriminates in favor of Group B, the resultant quality of their hires is almost unchanged.13

Affirmative action can have a small positive effect on hiring pool quality in theory, but only if discrimination in the other direction is extremely pervasive. Even then, the benefits from abandoning strictly merit-based hiring tend to be extremely small and fragile, evaporating as soon as other companies adopt merit-based hiring and reversing if other companies adopt similar affirmative action strategies.

Additionally, what’s very clear is that the more companies engage in affirmative action in favor of Group A, the better the results for companies that persist in discriminating against Group A. Not only does discrimination breed discrimination on a tit-for-tat identitarian basis, discrimination enables discrimination as a game theoretic exercise—because discrimination is an anti-coordination game.

The leaky pipeline & the backlash

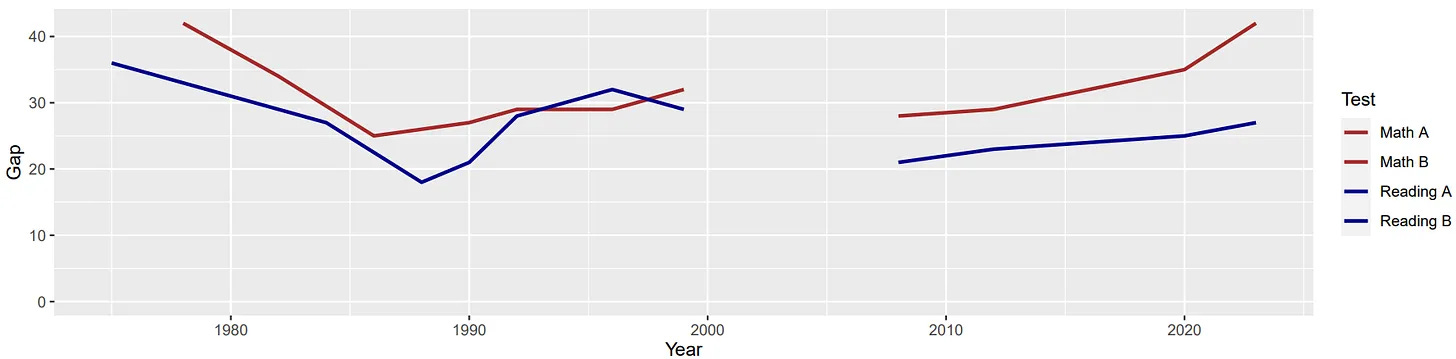

The core problem that affirmative action sought to address was that even after applying relentlessly blind meritocratic techniques to processes like hiring or college admissions, qualified candidates were still disproportionately unlikely to be African-American. While desegregation brought a decline in gaps in educational achievement, there are signs that the racial gap in K-12 educational achievement have increased since 1988.14

Affirmative action in hiring and college admissions were a way of achieving temporary results (greater visible representation on college campuses and in prestigious jobs) without fixing the underlying problem (achievement gaps that start in K-12 education, leading to a gap in qualified candidates). This backfires in three distinct ways:

The double standard reinforces a stereotype of an achievement gap.

Underqualified students fail out of challenging programs.

Double standards generate resentment.

A selective college that admits African-American students on the basis of lower standards of academic performance creates a class environment in which their students and professors experience a reality in which African-American students are less prepared and capable.

It is an environment in which negative stereotypes are accurate. It is an environment in which professors must either fail out African-American students at higher rates, grade them on a different curve, or lower the standards of instruction until few if any students fail at all.

The nepotism problem

We can’t talk about college admissions or the job market without talking about nepotism. Ivy League schools and other elite universities are known to give special consideration to legacy students and children of donors.15 Legacy admission was widely formally adopted by the Ivies as part of an effort to limit the influx of high-performing Jewish students in the 1920s.16 The problem was that Jewish students persistently scored better on entrance examinations.

In 2019, a major scandal broke: Many of the rich and privileged were cheating to get their kids into elite schools in a $25 million entrance exam cheating ring. Wealthy parents cannot simply buy a good SAT score.17 In 2020, a number of colleges and universities declared that they were dispensing with the SAT, a measure inspired by COVID-19. This was loudly celebrated by affirmative action advocates… and likely much more quietly by privileged parents whose children did poorly on the SAT. Proctored examinations are not perfect, but remain one of the best objective measures of talent.

While nepotism and affirmative action are sometimes discussed in terms of balancing factors in a calculus of racial politics,18 they have a synergetic relationship: Nepotism thrives in systems that are opaque, relying on subjective judgement of hard-to-quantify factors. Since explicit quotas and score-based systems providing a transparent advantage by race are strictly illegal, affirmative action requires non-transparent systems based on subjective discretion.19

Additionally, many negative impacts of nepotism and affirmative action are also synergistic. Both nepotism and affirmative action put downward pressure on quality standards, for example, leading to grade inflation. Both reduce social mobility and efficiency by limiting broad-based meritocratic access to elite institutions.

Finally, many of the individual beneficiaries of affirmative action come from economically privileged backgrounds, who know to highlight trace or non-existent minority heritage or who come from a global elite. They are identified with oppressed Americans who lived under Jim Crow laws symbolically rather than materially. For example, the now-infamous Claudine Gay came from a wealthy family that owns Haiti’s largest concrete plant and went to an elite boarding school; neither Gay nor even her ancestors were affected by Jim Crow.20

Recap and review

After three generations, there is no reason to expect race-based affirmative action to create any meaningful closure of any educational or economic gaps. Affirmative action as practiced widely and openly by both private and public universities for more than half a century is now thoroughly illegal, as is affirmative action in the corporate world. The Supreme Court had always viewed this as a temporary remedy at best, and affirmative action has decisively and clearly failed to meaningfully close population-level gaps between black and white Americans.

Even in the presence of widespread discrimination against a group, strictly merit-based selection is usually better for the institutions using it, and institutions adopting fashionable types of affirmative action can expect to reduce the quality of their selections as a result.

In addition to the failure of affirmative action to remedy the population-level gaps between black and white Americans, affirmative action has numerous second-order negative effects. Affirmative action supports and creates stereotypes of incompetence by people labeled as “affirmative action hires.” It also obscures the presence of urgent root problems that need addressing earlier in the pipeline, particularly in the domain of K-12 education.

Finally, the obscurity and reduction in emphasis on objective merit demanded by affirmative action processes also benefit well-connected and privileged candidates, as nepotism thrives in the darkness.

Notably, Yale and Princeton have released demographic data showing that the share of Asian-Americans admitted declined. Since the type of affirmative action practiced by Harvard and other Ivy League schools was found in particular to discriminate against Asian-American applicants, this suggests that these schools continue to discriminate against Asian-Americans.

It is also worth noting that while universities had an exception, this exception did not extend to hiring, but affirmative action (that is to say, discrimination in favor of groups seen as underrepresented) has remained commonplace in some sectors of the job market for decades.

See, for supporting evidence, the New York Times’s recent lengthy piece on DEI at the University of Michigan. The position that race-based affirmative action would be required on an indefinite basis would have been completely untenable by the ideological standards employed by the majorities in the Warren and Burger courts in the early key decisions.

Remaining gender gaps in income are related to career field, hours worked, educational attainment, and career duration; women work fewer hours, retire earlier, and tend choose fields with benefits and security rather than higher nominal salaries. Teachers, for example, are very poorly compensated in terms of nominal annual salary, but have high total compensation per hour. In some subgroupings, women earn more than men in raw compensation, explicable mainly by higher levels of educational attainment.

In the executive branch, the highest color barrier was broken in 2008 with the election of Barack Obama; in the legislative branch, there are about sixty African-American members of Congress, roughly proportionate to the African-American share of the population. In the private sector, there are ten African-American billionaires and eight African-American CEOs of Fortune 500 companies.

For example, the gap in home ownership rates by race increased from 1980 to 1990 and appears to have changed very little in the past 100 years; restricting to male-headed households in order to eliminate the effects of a separate pattern of a rising marriage gap shows the gap reached a minimum among comparable types of household around 1980, roughly one generation after the removal of formal discriminatory barriers began and two generations before the present time.

See in particular Bakke (1978) and the discussion therein about “remedial” preferences.

See, for example:

https://doi.org/10.1086/378526

https://doi.org/10.2307/2553676

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10888-019-09413-x

The major exception to this pattern of large-scale integration within three generations include religious groups with substantial lifestyle differences and racial minorities subjected to formally discriminatory policy, such as the Amish, a wave of early Chinese immigration that was formally curbed by the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, and a wave of early Japanese immigration that was informally curbed in 1907 and formally ended in 1924. Asian-Americans largely ceased to be an exception to this pattern following the removal of de jure racial discrimination.

Note that the period between desegregation of federal employees, begun in 1948, and the elimination of merit-based civil service examinations following a 1981 court case, marked another period of closing of this socioeconomic gap.

Harvard began actively working to reduce Jewish admissions in 1922.

This is equivalent to having a large number of companies that hire first.

Simulation details: Interviewed Quality as the sum of three normally-distributed Ability (mean = 50, sd = 15) + Noise (mean = 0, sd = 15). Pool of n=20000 cloned candidates whose only difference is group membership. Initial hire of 5000 candidates by Company 1, follow-up hire of 2000 candidates by Company 2.

Whether there is any advantage at all to discriminating in favor of Group B depends on parameters.

NAEP is one of the best long-term direct measures of the K-12 system, but similar patterns can be seen in SAT scores and other less direct measures. Note that 1988 would be 12 years after Runyon v. McCrary and 34 years after Brown v. Board; minimum racial gap corresponds to parents who had access to integrated public schools with children who entered school after Runyon v. McCrary banned private segregation academies.

As discussed in the SFFA v. Harvard / UNC cases, “legacy” admissions processes are even used in some public universities.

This was also accompanied by a reduced emphasis on admissions tests, geographic quota systems, et cetera—familiar features that have returned in the modern affirmative action era.

I could say a lot about the SAT—it’s a test I first took in 5th grade, so I had an unusual personal experience with it. However, the basic relevant point here is that the best preparation for the SAT is a good education in the fundamentals, with SAT-specific prep techniques having a marginal effect on top of major effects from skills in reading, reasoning, and mathematics. The best efforts of rich parents to improve their kid’s 1100 score are unlikely to push it to a 1300… without paying a ringer to illegally take the test in their place, at least.

Legacy admits in particular tend to be white, and a raft of “tit-for-tat” articles in progressive media called for the banning of legacy admissions following the SFFA v. Harvard case.

See Regents v. Bakke (1978), Gratz v. Bollinger (2003).

Preferential hiring for jobs via affirmative action was already illegal when Bakke (1978) was decided in favor of affirmative action for admissions purposes, but it is worth noting that affirmative action in favor of Claudine Gay would not have advanced any meaningfully remedial purpose.